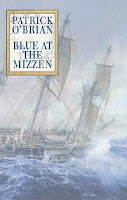

Recent reading includes the last of Patrick O'Brian's glorious sea novels, Blue at the Mizzen, which I read with real regret that there are no more to come (I will not read "21," tugged out of O'Brian's notes).

Recent reading includes the last of Patrick O'Brian's glorious sea novels, Blue at the Mizzen, which I read with real regret that there are no more to come (I will not read "21," tugged out of O'Brian's notes).I vividly recall my first encounter with O'Brian in a used bookstore on Valencia Street in San Francisco in 1998 or 1999: the book (Master and Commander) caught my eye, in one of those happy accidents you come to wish with all your heart had happened years before; I pulled it off the shelf, crouched on my heels to get out of other customers' hair, opened the book, and over an hour later realized that my knees were close to permanently locked in their deep bend -- so utterly had the book pulled me into its world. (I reacted the same way a couple of years later to J.G.A. Pocock's Machiavellian Moment, when I lifted it out of its Amazon box on the floor of my study, a few blocks away from that bookstore, and came up for air in a state of shocked excitement hours later.)

Fellow discoverers will recognize that first thrill of meeting the Aubrey/Maturin pair (which I am far from the first to write about). Put all thoughts of the movie out of your head:

The music-room in the Governor's House at Port Mahon, a tall, handsome, pillared octagon, was filled with the triumphant first movement of Locatelli's C major quartet. The players, Italians pinned against the far wall by rows and rows of little round gilt chairs, were playing with passionate conviction as they mounted towards the penultimate crescendo, towards the tremendous pause and the deep, liberating final chord. And on the little gilt chairs at least some of the audience were following the rise with an equal intensity: there were two in the third row, on the left-hand side; and they happened to be sitting next to one another. The listener farther to the left was a man of between twenty and thirty whose big form overflowed his seat, leaving only a streak of gilt wood to be seen here and there. He was wearing his best uniform--the white-lapelled blue coat, white waistcoat, breeches and stockings of a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, with the silver medal of the Nile in his buttonhole--and the deep white cuff of his gold-buttoned sleeve beat the time, while his bright blue eyes, staring from what would have been a pink-and-white face if it had not been so deeply tanned, gazed fixedly at the bow of the first violin. The high note came, the pause, the resolution; and with the resolution the sailor's fist swept firmly down upon his knee. He leant back in his chair, extinguishing it entirely, sighed happily and turned towards his neighbour with a smile. The words 'Very finely played, sir, I believe' were formed in his gullet if not quite in his mouth when he caught the cold and indeed inimical look and heard the whisper, 'If you really must beat the measure, sir, let me entreat you to do so in time, and not half a beat ahead.'

Jack Aubrey's face instantly changed from friendly ingenuous communicative pleasure to an expression of somewhat baffled hostility: he could not but acknowledge that he had been beating the time; and although he had certainly done so with perfect accuracy, in itself the thing was wrong.

No comments:

Post a Comment